Reflections on the Underground Railroad

By Charles L. Blockson

Though Forty Years have passed, I remember as if it were yesterday the moment when the Underground Railroad in all its abiding mystery and hope and terror took possession of my imagination. It was a Sunday afternoon during World War II; I was a boy of ten, sitting on a box in the backyard of our home in Norristown, Pennsylvania, listening to my grandfather tell stories about the family.

Charles L. Blockson[1]

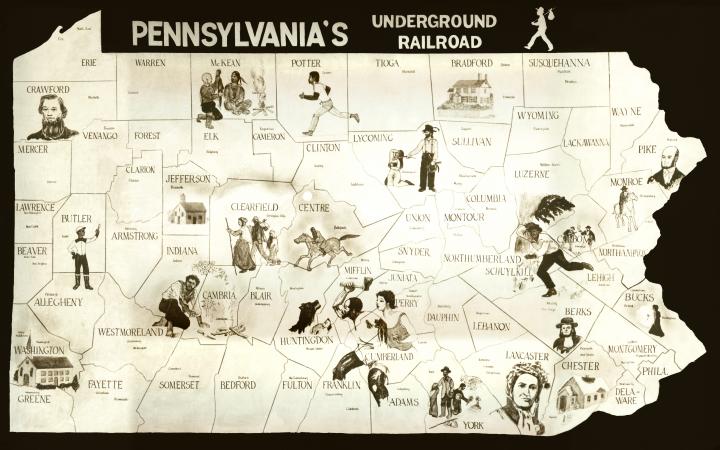

(Original map design: oil on canvas, by Charles Hollingsworth, 1981. Image courtesy of the permanent collection of the African American Museum in Philadelphia)

Introduction

In the year 2012, the history of Black Philadelphians still remains little known to most Americans. I am hopeful that the creation of the current site on William Still, made possible through by a federal Save America’s Treasures Grant administered by the National Endowment for the Humanities and Temple University Libraries, will be an educational tool for teachers, students and the general public to examine the rich history of African Americans. Among the many original manuscripts in the Blockson Collection are the letters of William Still. In one letter that William Still wrote to his daughter dated August 13, 1867, he writes that he is, “reading Macaulay’s History of England with great interest,” and that he intends “to write the History of the U.G.R.R. “ He continued, “I must do a good deal of reading and thinking in order to be able to write well. I may commence my book this fall some time.” His book, The Underground Railroad, was published in 1872. His book was a major inspiration for my research and writing. In the following essay, I would like to share some history related to The Underground Railroad, William Still and Black Philadelphians that I discovered during my many years of research.

During my research, I found a family connection between my family and the Still family. Our family relationship extends almost 170 years. I learned after contacting the National Archives for information on William N. Blockson, the son of Leah Blockson, my great-grandmother. William married Henrietta G. Still of Philadelphia on July 4, 1869 and that she was the daughter of William Still’s brother . When the William Still Collection was donated to the Blockson Collection by the Still family, I was surprised to learn that William Still was also one of the antebellum black collectors and bibliophiles along with Robert Purvis, Dr. Robert Campbell, Isaiah C. Wears, William Carl Bolivar, William Whipper, and John S. Durham. Clarence Still, the present patriarch of the Still family, bestowed me with the position of honorary chairman of the Annual Still Day Family Reunion, held for over 140 years in Lawnside, New Jersey, once known as Snow Hill. During one of the reunions, more than three hundred descendants of William Still and his brothers gathered around me and sung a song that I wrote in my 1983 book entitled the “Ballad of the Underground Railroad".

By the year 1984, I had spent more than 40 years conducting research and writing about the mystery, hope and terror associated with the Underground Railroad. That year, National Geographic published my article in its July issue. The article, entitled “Escape from Slavery: The Underground Railroad” brought attention to its significant role in African resistance to slavery. I wrote about my grandfather’s narrative to me:

“My father—your great-grandfather, James Blockson—was a slave over in Delaware,” Grandfather said, “but as a teenager he ran away underground and escaped to Canada.” Grandfather knew little more than these bare details about his father’s flight to freedom, for James Blockson, like tens of thousands of other black slaves who fled north along its invisible rails and hid in its clandestine stations in the years before the Civil War, kept the secrets of the Underground Railroad locked in his heart until he died.”[2]

My grandfather also told me about Jacob Blockson, my great-grandfather’s cousin, who also escaped on the Underground Railroad. Years later, I would read his account in William Still’s classic book, The Underground Railroad as well as the name of my great-grandfather James. My grandfather provided the following account about Jacob Blockson:

“So did his cousin Jacob Blockson, who escaped to St. Catharines, Ontario, in 1858, two years after my great-grandfather’s journey to the promised land, as runaway slaves sometimes called Canada. But Jacob told William Still, a famous black agent of the Underground Railroad in Philadelphia, the reasons for his escape: ‘My master was about to be sold out this Fall, and I made up my mind that I did not want to be sold like a horse….I resolved to die sooner than I would be taken back.’”[3]

When I was 15 years old, I travelled from Norristown to Philadelphia to browse in some bookstores. At Leary’s Book Store at 9th and Market Streets, I found a thick, worn green cloth-covered book entitled The Underground Railroad by William Still published in 1872. I paid five dollars for the book. The book was much more than I had bargained for as I found two of my relatives who escaped on the Philadelphia’s Underground Railroad. The discovery of William Still’s book began my interest in the history of the Underground Railroad which led me to write about it. Still’s book contained the following information:

Jacob Blockson was a stout and healthy-looking man, about twenty-seven years old, with a countenance indicative of having no sympathy for slavery. Being invited to tell his own story, describe his master, etc., he unhesitatingly relieved himself somewhat after this manner:

“I escaped from a man by the name of Jesse W. Paten [Layton]; he was a light complected man, tall, large, and full-faced, with a large nose. He was a widower. He belonged to no society of any kind. He lived near Seaford, in Sussex County, Delaware.

I left because I didn’t want to stay with him any longer. My master was about to be sold out this Fall, and I made up my mind that I did not want to be sold like a horse, the way they generally sold darkies then; so when I started I resolved to die sooner than I would be taken back; this was my intention all the while.

I left my wife, and one child; the wife’s name was Lear [Leah], and the child was called Alexander. I want to get them on soon too. I made some arrangements for their coming if I got off safe to Canada.”[4]

Jacob Blockson, after reaching Canada, true to the pledge that he made, wrote back as follows:

Saint Catharines, Canada West, Dec. 26th, 1858.

DEAR WIFE: -- I now inform you I am in Canada and am well and hope you are the same, and would wish you to be here next August. You come to suspension bridge and from there to St. Catharines, write and let me know. I am doing well working for a Butcher this winter, and will get good wages in the spring. I now get $2.50 a week.

I Jacob Blockson, George Lewis, George Alligood and James Alligood are all in St. Catharines, and met George Ross from Lewis Wright’s, Jim Blockson is in Canada West, and Jim Delany, Plunnoth Connon. I expect you my wife Lea Ann Blockson, my son Alexander & Lewis and Ames will all be here and Isabella also, if you cant bring all bring Alexander surely, write when you will come and I will meet you in Albany. Love to you all, from your loving Husband,

Jacob Blockson[5]

My article made the cover story on National Geographic Magazine and our nation and the world were re-introduced to the courage and determination of enslaved Africans who escaped on the Underground Railroad. I wrote in my article of the Underground Railroad that: “It was a network of paths through the woods and fields, river crossings, boats and ships, trains and wagons, all haunted by the specter of recapture. Its stations were the houses and churches of men and women—agents of the railroad—who refused to believe that human slavery and human decency could exist together in the same land.”[6]

During January 1990, I was contacted by U.S. Representative Peter H. Kostmayer. On January 15, 1990, a news conference was held at Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church in Philadelphia with me and United States Representative Peter Kostmayer. At the meeting, we discussed the proposed federal legislation to formally identify and preserve historic sites connect with the Underground Railroad and to designate them as part of an Underground Railroad Historic Trail. That same year, I was selected to Chair an Advisory Committee when Congress Passed Public Law 101-628, recognizing the significance of the Underground Railroad to American history. The legislation directed the Secretary of Interior and the National Park Service to conduct a study of the Underground Railroad. From the beginning Pennsylvania was instrumental in the start of the process for the original proposal. Our Committee examined the historical significance of various sites existing in 23 states and territories, which included links to Canada, Mexico and the Caribbean Islands. The Advisory Committee’s first meeting was held in Independence Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. As a result of our work, President William Jefferson Clinton signed the National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom Act into law on July 21, 1998.

Black Philadelphians

Most heroic of all were the slaves and free blacks who offered their churches and their homes to help the enslaved—and above all, the passengers themselves.[7]

The City of Philadelphia was a center where anti-slavery roots were planted and nurtured many years before the 1800’s. Pennsylvania Abolition Society was founded in 1775. Its members included Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, Dr. Benjamin Rush and Marquis de Lafayette. These friends of enslaved Africans were the first to popularize and to lobby for total abolition of slavery. Philadelphia became a vital junction on the Underground Railroad. It was important because there was an international port in the city. Men and women, young and old, from all races, religions, and walks of life kept the “Freedom Train” rolling. William Still was among the brave and courageous Black Philadelphians who participated in the dangerous mission of assisting to liberate enslaved Africans. Others participants, both White and Black, included The Reverend Richard Allen and Sarah Allen, Passmore Williamson, J. Miller McKim, Robert Purvis, Lucretia Mott, Jacob Blockson, Henry “Box” Brown, Charles and Joseph Bustill, William and Ellen Craft, Isaac Hopper, Samuel Johnson and family, and Lear Green, who at the age of 18 years old, was sent from Philadelphia to Elmira, New York to gain her freedom.

I have spent many years writing about Blacks in Pennsylvania, especially Black Philadelphians. As early as 1787, the black community in Philadelphia formed the Free African Society, an organization for mutual aid. Two important Black churches grew from this society: the Mother Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church, founded by Richard Allen and the African Church of St. Thomas, founded by Absalom Jones. Their churches became centers of spiritual and political life in the antebellum black community in Philadelphia. Both pastors were involved in the Underground Railroad. Bishop Allen and his wife, Sarah, assisted hundreds of enslaved Africans. They hid them in their church as well as their home, providing them with food, shelter and protection.

Philadelphia became the “antebellum capitol” of the northern free Black population. Interestingly, the onset of antislavery activities and fugitive aid in 1833 coincided with the emergence of educational and social self-improvement movements within Black communities in Pennsylvania. By the 1830’s, a majority of Black clergy in Philadelphia permitted abolitionists and fugitive aid meetings and activities in their churches. They also joined the abolitionist movement. For example, the Zoar A.M.E. Church in Northern Liberties held a public meeting on April 16, 1838 to solicit contributions and increase membership for the Vigilant [Fugitive Aid] Association and Committee. The Black clergy was also involved in the Underground Railroad such as The Reverend Walter Proctor, pastor of Mother Bethel A.M.E. Church, who was an agent. He also belonged to the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. Other reverends connected with the Underground Railroad were Reverend Stephen H. Gloucester, pastor of Central Presbyterian Church of Color, Reverend Charles L. Gardiner, Reverend Daniel Scott, pastor of the Union Baptist Church, and Reverend William Douglass. Reverend John T. Moore, pastor of the Wesley African Methodist Episcopal Church used his church as a safe house for fugitives. Campbell African Methodist Church helped enslaved Africans escape. The religious community also spearheaded the Free Produce Movement, urging concerned citizens in the North to refrain from using products of slave labor. The Black clergy’s activities were a direct challenge to the prevailing religious dogma of many white churches that a truly religious person was patient, even with slaveholders.

Black abolitionists assumed leadership in reform organizations. James Forten, one of Philadelphia’s most influential black residents, was active in many political causes and committed to the abolitionist movement. When William Lloyd Garrison launched his anti-slavery newspaper, The Liberator, Forten not only encouraged him but also contributed money towards the publication. In 1833, Forten’s daughter Harriet Forten was one of the founders of the Female Anti-Slavery Society in Philadelphia. Her husbandRobert Purvis was known as the president of the Philadelphia Underground Railroad. That same year, Purvis became a charter member of the American Anti-Slavery Society and served as president and vice president of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee and the Pennsylvania Anti-Slavery Society. Numerous fugitives were given shelter at his mother’s home, Harriet Judah Purvis, located at Ninth and Lombard Streets. Robert Purvis’ brother, Joseph Purvis, who married Forten’s daughter, Sarah Louise Forten, was also involved in Underground Railroad activities in Bucks County. William Whipper’s accounts of Joseph Purvis’ activities in the Underground Railroad are recorded by William Still. In 1838, Robert Purvis published his famous Appeal of Forty Thousand Citizens, Threatened with Disfranchisement, To the People of Pennsylvania, in response to the state’s legislature law prohibited blacks from voting. Jacob C. White Sr. and his son Jacob Jr. used their home at 100 Old York Road as a Underground Railroad station.

During August 1835, the more militant black and white abolitionists created the Philadelphia Vigilance Association “to fund aid to colored persons in distress.” The Committee assisted destitute enslaves Africans with room and board, clothing medicine, and money as well as gave them knowledge of their legal rights, legal protection from kidnappers and prosecuted individuals who attempted to kidnap or violate the legal rights of free Blacks. The association also helped runaways set up permanent homes and/or gave them temporary employment before their departure to Canada. The association elected three African American officers at its initial meetings, including James McCrummell, President; Jacob C. White Jr, Secretary, and James Needham, Treasurer. John C. Bowers was also a member. Overtime, a majority of the officers in the association were African Americans. For example, in 1839, out of the 16 members, the nine African Americans included James McCrummell, Jacob C. White, James Needham, James Gibbons, Daniel Colly, J.J. G. Bias, and Shepherd Shay. William Still, Robert Purvis, Charles H. Bustill, Charles Reason and Joseph C. Ware also became members.

Underground Railroad lore in Philadelphia provides modern readers with Robert Purvis destroyed many of his records of the Vigilance Association of Philadelphia so that members would not be prosecuted for breaking federal law nor did he want escapees recaptured. A friend of Purvis, William Still, was secretary of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee. Still did not destroy his records. A visionary, he hid the committee’s paper in the loft of a building on the grounds of the Lebanon Cemetery. Jacob C. White Sr.’s office at the Lebanon Cemetery was also a station stop, communication center and distribution point for anti-slavery newspapers. Still’s motive in hiding the paper was to use the records to help reunite relatives and friends. According to his journal, the committee assisted over 495 runaway slaves between December 1852 and February 1857. When he published his classic book, The Underground Railroad, he covered eight years of assisting fugitives. His book contains approximately 800 recorded accounts of escaped slaves, including 60 children. Still and his co-workers thoroughly questioned all enslaved Africans who escaped bondage as well as the strangers who came to them for assistance. This was done to protect the vast network of agents from spies and imposters who would expose secret operations for either fame or money.

William Still is one among many courageous men and women who were willing to stand up for justice and equality. This meant that they were committed to end the system of slavery. I have many reflections on the Underground Railroad. I hope that this brief essay stimulates your intellectual curiosity to visit the Charles L. Blockson Afro-American Collection to learn more about the Underground Railroad.

[1] “Escape From Slavery: The Underground Railroad, National Geographic Magazine, Page 3

[2] Ibid, Page 3

[3] Ibid

[4] Ibid.

[5] William Still, The Underground Railroad. A Record of Facts, Authentic Narratives, Letters, &c., Narrating the Hardships Hair-breadth Escapes and Death Struggles of the Slaves in their efforts for Freedom, As Related By Themselves and Others, or Witnessed By the Author; Together With Sketches of some of the Largest Stockholders, and Most Liberal Aiders and Advisers, of the Road, Philadelphia: Porter & Coates, 1872, Page 490-491.

[6] “Escape From Slavery: The Underground Railroad, National Geographic, Page 3

[7] Ibid, Page 10

To learn more about William Still, please see:

- The Life and Times of William Still

- William Still's Contemporaries

- Links to related websites, including links to William Still's books

- View William Still's family photographs, correspondence, and related primary source materials by Searching the Collections